Word Embeddings for Natural Language Processing

Word embedding is a technique that treats words as vectors whose relative similarities correlate with semantic similarity. This technique is one of the most successful applications of unsupervised learning. Natural language processing (NLP)systems traditionally encode words as strings, which are arbitrary and provide no useful information to the system regarding the relationships that may exist between different words. Word embedding is an alternative technique in NLP whereby words or phrases from the vocabulary are mapped to vectors of real numbers in a low-dimensional space relative to the vocabulary size, and the similarities between the vectors correlate with the words’ semantic similarity.

Word embedding is a technique that treats words as vectors whose relative similarities correlate with semantic similarity.

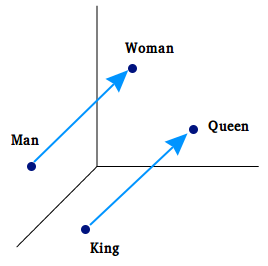

For example, let’s take the words woman, man, queen, and king. We can get their vector representations and use basic algebraic operations to find semantic similarities. Measuring similarity between vectors is possible using measures such as cosine similarity. So when we subtract the vector of the word man from the vector of the word woman, then its cosine distance would be close to the distance between the word queen minus the word king (see Figure 1).

W("woman")−W("man") ≃ W("queen")−W("king")

Many different types of models were proposed for representing words as continuous vectors, including latent semantic analysis (LSA) and latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA). The idea behind those methods is that words that are related will often appear in the same documents. For instance, backpack, school, notebook, and teacher are probably likely to appear together. But school, tiger, apple, and basketball would probably not appear together consistently. To represent words as vectors--using the assumption that similar words will occur in similar documents--LSA creates a matrix whereby the rows represent unique words and the columns represent each paragraph. Then LSA applies singular value decomposition (SVD), which is used to reduce the number of rows while preserving the similarity structure among columns. The problem is that those models become computationally very expensive on large data. Instead of computing and storing large amounts of data, we can try to create a neural network model that will be able to learn the relationship between the words and do it efficiently.

Word2Vec

The most popular word embedding model is word2vec, created by Mikolov et al. in 2013. The model showed great results and improvements in efficiency. Mikolov et al. presented the negative-sampling approach as a more efficient way of deriving word embeddings. You can read more about it here. The model can use either of two architectures to produce a distributed representation of words: continuous bag-of-words (CBOW) or continuous skip-gram.

We’ll look at both of these architectures next.

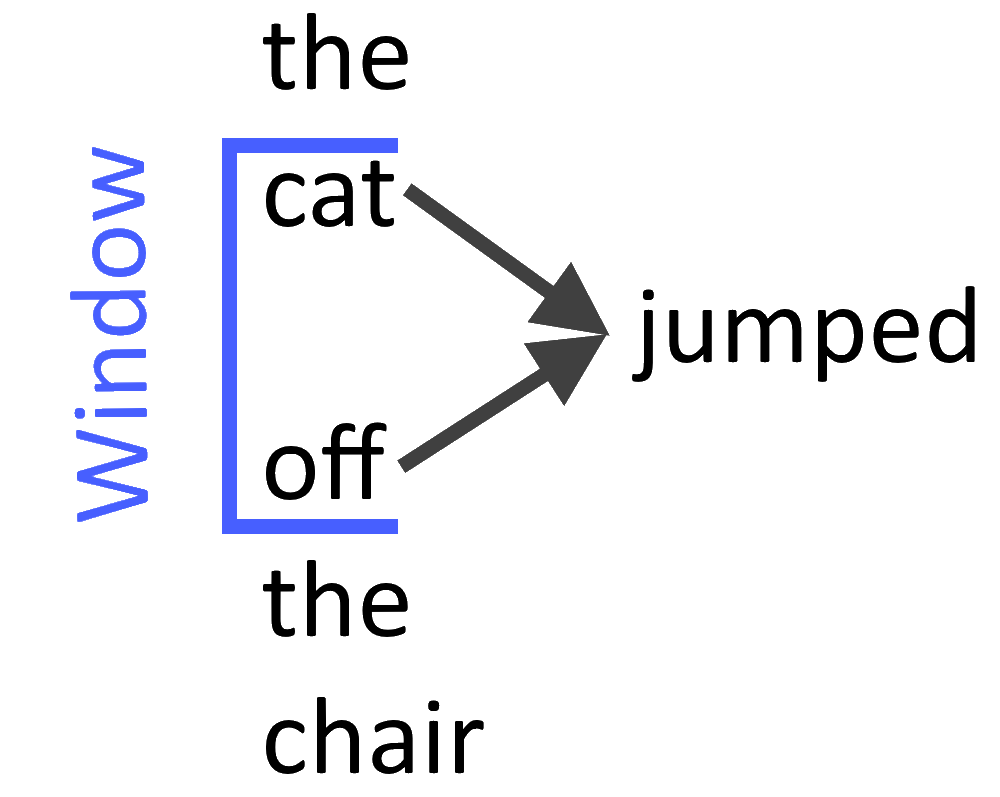

Continuous bag-of-words (CBOW)

A sequence of words is equivalent to a set of items. Therefore, it is also possible to replace the terms word and item, which allows for applying the same method for Collaborative Filtering and recommender systems. CBOW is several times faster to train than the skip-gram model and has slightly better accuracy for the words that appear frequently (see Figure 2).

Predicting the word given its context

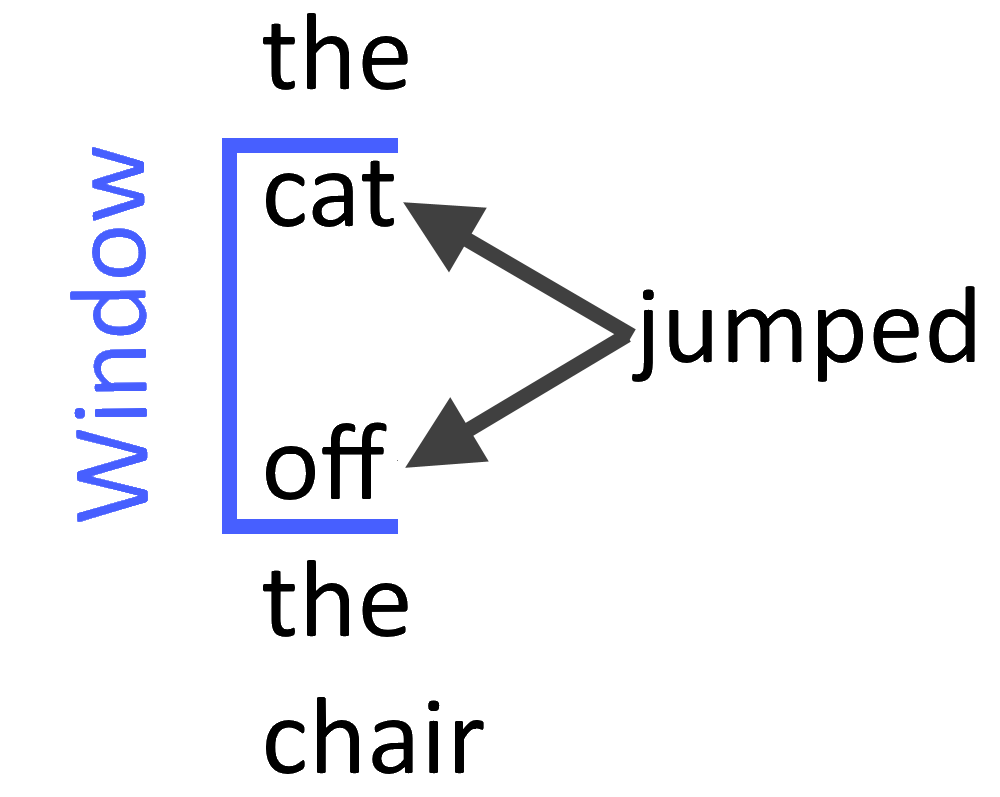

Skip-gram

Predicting the context given a word

Coding

You can find the code for the following example at GitHub repo: liorshk/wordembedding

The great thing about this model is that it works well for many languages.

All we have to do is download a big dataset for the language that we need.

Looking to Wikipedia for a big dataset

- Find the ISO 639 code for your desired language: List of ISO 639 codes

- Go to: https://dumps.wikimedia.org/{{LANGUAGE CODE}}wiki/latest/

- Download {{LANGUAGE CODE}}wiki-latest-pages-articles.xml.bz2

pip install --upgrade gensimWe need to create the corpus from Wikipedia, which we will use to train the word2vec model. The output of the following code is "wiki.{{LANGUAGE CODE}}.text"--which contains all the words of all the articles in Wikipedia, segregated by language.

from gensim.corpora import WikiCorpus

language_code = "he"

inp = language_code+"wiki-latest-pages-articles.xml.bz2"

outp = "wiki.{}.text".format(language_code)

i = 0

print("Starting to create wiki corpus")

output = open(outp, 'w')

space = " "

wiki = WikiCorpus(inp, lemmatize=False, dictionary={})

for text in wiki.get_texts():

article = space.join([t.decode("utf-8") for t in text])

output.write(article + "\n")

i = i + 1

if (i % 1000 == 0):

print("Saved " + str(i) + " articles")

output.close()

print("Finished - Saved " + str(i) + " articles")

Training the model

The parameters are:- size: The dimensionality of the vectors (bigger size values require more training data, but can lead to more accurate models)

- window: The maximum distance between the current and predicted word within a sentence

- min_count: Ignore all words with total frequency lower than this.

import multiprocessing

from gensim.models import Word2Vec

from gensim.models.word2vec import LineSentence

language_code = "he"

inp = "wiki.{}.text".format(language_code)

out_model = "wiki.{}.word2vec.model".format(language_code)

size = 100

window = 5

min_count = 5

start = time.time()

model = Word2Vec(LineSentence(inp), sg = 0, # 0=CBOW , 1= SkipGram

size=size, window=window, min_count=min_count, workers=multiprocessing.cpu_count())

# trim unneeded model memory = use (much) less RAM

model.init_sims(replace=True)

print(time.time()-start)

model.save(out_model)FastText

Facebook’s Artificial Intelligence Research (FAIR) lab recently released fastText, which is a library that is based on the paper: Enriching Word Vectors with Subword Information. The difference from word2vec is that each word is represented as a bag of character n-grams. A vector representation is associated to each character n-gram and words are being represented as the sum of these representations.Using Facebook's new library is easy:

pip install fasttext

Training the model:

start = time.time()

language_code = "he"

inp = "wiki.{}.text".format(language_code)

output = "wiki.{}.fasttext.model".format(language_code)

model = fasttext.cbow(inp,output)

print(time.time()-start)Evaluating Embeddings: Analogies

We would like to evaluate the models by testing them on our previous exampleW("woman") ≃ W("man")+ W("queen")− W("king")After that, it calculates the dot product between the vector representation of all the test_words and the weighted average.

In our case, the test words is all the vocabulary. At the end we print the word that had the highest cosine similiarity with the weighted average of the positive and negative words.

import numpy as np

from gensim.matutils import unitvec

def test(model,positive,negative,test_words):

mean = []

for pos_word in positive:

mean.append(1.0 * np.array(model[pos_word]))

for neg_word in negative:

mean.append(-1.0 * np.array(model[neg_word]))

# compute the weighted average of all words

mean = unitvec(np.array(mean).mean(axis=0))

scores = {}

for word in test_words:

if word not in positive + negative:

test_word = unitvec(np.array(model[word]))

# Cosine Similarity

scores[word] = np.dot(test_word, mean)

print(sorted(scores, key=scores.get, reverse=True)[:1])Testing it on FastText and gensim's Word2vec:

positive_words = ["queen","man"]

negative_words = ["king"]

# Test Word2vec

print("Testing Word2vec")

model = word2vec.getModel()

test(model,positive_words,negative_words,model.vocab)

# Test Fasttext

print("Testing Fasttext")

model = fasttxt.getModel()

test(model,positive_words,negative_words,model.words)Testing Word2vec ['woman'] Testing Fasttext ['woman']Which means that it works both on fasttext and gensim's word2vec!

W("woman") ≃ W("man")+ W("queen")− W("king")And as you can see, the vectors actually capture the semantic relationship between the words!

The ideas presented by the models that we described can be used for many different applications, allowing businesses to predict the next applications they will need, perform sentiment analysis, represent biological sequences, perform semantic image searches, and more.

Thank you for reading!

For any questions feel free to contact me: lior@deep-solutions.net

Deep Solutions wishes you a great deep day!